The wrong kind of fear

Risk: We are surrounded by dangers. Terrorism, air crashes, contaminated food – these all cause us fear. But maybe we should actually be afraid of completely different things.

On September 11, 2001, 256 passengers lost their lives in the airplanes used in the terrorist attacks in the United States. During the following year, an alarming after-effect was observed. In 2002, statistics showed a drastic increase of 1,600 in the number of road traffic fatalities – about 4 percent more. “Out of fear, many people avoided airplanes and used their cars instead. The increase in traffic resulted in more road accidents. And consequently more deaths,” explains Professor Gerd Gigerenzer, Director of the Harding Center for Risk Literacy, Berlin, Germany. Shocked by the attacks, people now perceived air travel as very dangerous. “Paradoxically, we have hardly any fear of dying in an accident, but we are more afraid of perishing along with many others – as in an aircraft or a terrorist attack,” Gigerenzer says. We disregard the fact that we have already put the – statistically – most dangerous part of the journey behind us when we leave our car in the parking lot at the airport.

Subjective fear strongly differs from factual reality, which can be substantiated with figures and statistics.”

Their feeling tells people they are more in control behind the steering wheel of their own car than in a plane flown by a pilot. “And a controllable risk seems less dangerous than an uncontrollable one,” says Paul Slovic, a professor of psychology at the University of Oregon, USA, and one of the leading experts in risk perception. However, in the first years following the attacks, not a single deadly accident happened during commercial flights in the United States.

The risk of tornados in the United States is especially high from March through July. This tornado raged through Campo, Colorado, in May 2010.

A sense of reality looks different

Epidemics, terrorist attacks, plane crashes – people nowadays often rate risks higher than they should. They suffer from an emotional imbalance. “It’s difficult for people to assess risks correctly. Their subjective fear strongly differs from factual reality, which can be substantiated with figures and statistics,” Gigerenzer says.

A controllable risk seems less dangerous than an uncontrollable one.”

People today are afraid of dangers that either do not exist at all for them or are very unlikely – for dangers are one thing, but the probability that they will actually happen is something else. A lion is certainly dangerous, but if it is captive in a zoo the danger to humans is relatively low. “Our lives are more low-risk than ever, and dangers often seem more threatening to us than they actually are,” says Professor Ortwin Renn, Scientific Director at the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS) in Potsdam, Germany, who has worked extensively on the topic of risk perception. Paradoxically, this fear is intensified by the fact that we are so well off and everything is actually fine. “That is because this naturally also means we have a lot to lose,” Renn says. In saturated societies such as those of the Western industrialized nations, he explains, people have correspondingly more fear than in less developed societies, where individuals expect to make personal progress by taking risks.

Exercise caution

Irrationality is international

There are many reasons for our incorrect assessments. Our perception of risk is influenced by feelings, not by our intellect. Thus our assessment of probabilities is different from the statistical reality. “Most risk analysis in daily life is handled quickly and automatically by feelings arising from what is known as the ‘experiential’ mode of thinking,” Slovic says. The fact that we repeatedly also experience improbable things and that the media report on them confirms us in our belief that improbable things may not be so improbable after all. That is an error in reasoning. The thing that we fear most is probably the thing that we are most unlikely to experience.

Social and cultural factors also play a big part in what frightens us. Nevertheless, irrationality is international. It is universally true that the risk of rare and spectacular things such as tornados, air crashes or terrorist attacks is overrated, while more probable causes of death are overlooked. Risk expert Slovic has identified two more factors. If someone takes a risk by choice, he’ll perceive it as less dangerous than a risk forced upon him. The greatest dangers, however, are met with indifference – high blood pressure, obesity, alcohol, smoking. Also, a high-fat diet is wrongly considered more low-risk than genetically modified food.

Danger of death in perspective

One micromort equals a one-in-a-million probability of dying. This unit of risk measurement is credited to Professor Ronald A. Howard, Stanford University, USA.

Selected risks in the United Kingdom or for marathons, in the USA.

Source: The Norm Chronicles, Michael Blastland and David Spiegelhalter, 2013

“What people know, or think they know, often does not frighten them,” Renn says. Similarly, many people are more anxious about the risks of new technologies than the risks of familiar ones. However, fear of the unknown, or technophobia, is not a good adviser, for responsibly managed risk means innovation, progress and, consequently, improved living conditions. Giving up these effects entails a high risk for society. Harboring reservations about the unknown therefore means high indirect costs.

The fact that we assess dangers wrongly is also related to modern technology. Modern methods of analysis can identify the smallest impurities. Scientists are now literally able to find needles in haystacks – one molecule among a septillion of others. To express this in a tangible way, a single grain of rye can now be identified in a 20,000-kilometer-long freight train full of grains of wheat. The same applies, of course, to any trace of poison, however small, even though it often would have no consequences for the organism. After all, it is the dosage that makes it a poison – or, indeed, a medicine. For example, botulinum toxin, better known as botox, is the most poisonous substance that nature produces. One tablespoon would be enough to poison the whole of Europe, the German Neurological Society has calculated as a mental exercise. Nevertheless, many people voluntarily have this neurotoxin injected under their skin or use it medicinally for cramps, spasms or excessive perspiration. This is because in greatly diluted form – a tiny bottle contains only one-billionth of a gram of the poison – and correctly used, the benefit is greater than the possible risks or side effects.

Culture of fear

The risks that people fear also depend on their culture and society, says the Japanese risk researcher and founding director of Litera Japan Co, Mariko Nishizawa.

Risk researcher and founding director, Tokyo, Japan

Risk perception

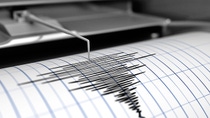

Risk perception always depends on the context. If people are constantly hearing news items about the spread of viruses, they are more likely to believe that they, too, could get infected. By contrast, if they are used to certain risks, they will regard those as not so dangerous. For example, the Japanese have lived with earthquakes for generations, and so are much more relaxed about the risk of earthquakes than, say, Germans, who have scarcely any knowledge of earthquakes from their own experience.

Food quality

By contrast, the Japanese are very sensitive about the quality of their food. They do not like it to contain any artificial additives or added colors. Americans, however, tolerate artificial additives that enable food to be kept longer. Hormone treatments for animals are also taboo in Japan, as they are in many European countries. In the United States, though, they are regularly given to animals. Therefore, it is evident that what people reject as risky varies by culture.

New technologies

This is also made clear in attitudes to technological innovations. In Germany, risks are investigated at an early stage. People are aware that there is no such thing as a 100 percent risk-free technology – and they are, therefore, often hesitant and cautious about taking new, unfamiliar paths. This may be a small reflection of the old German angst. Americans, by contrast, are open to technological progress. In Japan, too, high-end technology is overwhelmingly valued and is already being used on a huge scale – from high-speed trains that run on time to robots at hotel reception desks.

Top 5 most poisonous substances

Poisons

Four of the five most poisonous substances are found in nature and one is a by-product of industry.

Figures given are LD50-Value

This means that if laboratory animals such as rats or mice are given the amount of the substance shown below per kilogram of body weight, 50 percent of them will die.

Botulinum toxin A (natural)

Source: Clostridium botulinum bacterium

0.00000003 mg

Tetanus toxin A (natural)

Source: Clostridium tetani bacterium

0.000005 mg

Diphtheria toxin (natural)

Source: Corynebacterium diphtheriae bacterium

0.0003 mg

Dioxin (synthetic)

Source: By-products of incineration in industry

0.03 mg

Muscarin (natural)

Source: various types of mushroom

0.2 mg

Source: The Extraordinary Chemistry of Ordininary Things, Carl H. Snyder, 2003

Flood of information alters perception of risk

Alongside the greater precision of analysis, there is also a glut of media-generated information about dangers that is changing perceptions. News constantly rains down on us from all corners of the globe. This news actually affects individuals only rarely, but it has a huge impact on our perception of risk. Especially in relation to the discovery of chemicals in food, one shock wave seems to follow another. Although critical reporting is fundamentally important, it often turns out, when viewed calmly, to have been about something far from the level at which a danger would exist. By contrast, one of the biggest risk factors in relation to food lies in an area that attracts little public attention: consumers’ hygiene habits, as the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment is repeatedly pointing out.

We have to learn how we process risk in order to handle it more appropriately in the future.”

Across Germany, the Campylobacter bacterium is now the most common cause of intestinal infection, with more than 70,000 documented cases a year, and the true figure could be much higher. However, hardly anybody knows about it, and this pathogenic bacterium has so far rarely featured in the media. However, Campylobacter is found on nearly every chicken and is therefore also present on other pieces of meat that are roasted or grilled. Often, all that it takes to cause an infection is for a raw piece of chicken to be placed on the grill and for the same hand then to touch a cooked sausage.

Risk as a political issue

The more unsettled the public are, the harder it becomes for policymakers to maintain a rational course. This is demonstrated repeatedly in relation to controversial topics such as food safety, nuclear power or green genetic engineering. Risk awareness is a good weapon against such a nervous atmosphere. “Only if we learn how we ourselves process risk and draw appropriate, realistic conclusions from information about risk will we have the means to assess risk better in the future and to handle it more appropriately,” Renn says. There is no way of avoiding this, the risk researcher stresses. “Risk is part of our lives.”

Fiddling with figures

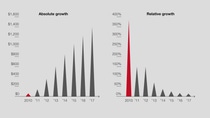

Manipulated: There are many opportunities for distortion when dealing with figures. Their graphic presentation, in particular, has a big influence on the conclusions we draw from them. Here are three examples showing how designers of infographics manipulate information.