Novice in mediji

Fragrance makers

Smells influence our senses, our thinking and our metabolism. How they are produced synthetically is just as fascinating. One single odorant is the source of the scent of lavender, roses or mint.

Anyone who pokes their nose into the BASF Visitor Center in Ludwigshafen on the Rhine, Germany, is in for a sensory surprise. Just press a button on a glass flask, and you will immediately be hit by an aroma reminiscent of lavender. However, this scent that might remind you of sundrenched Provence in France is actually a replica – a combination of the synthetic fragrances linalool and linalyl acetate.

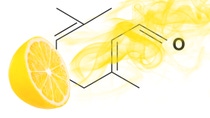

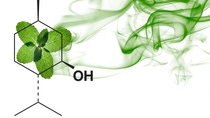

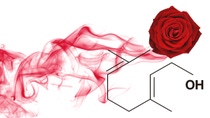

“It is actually a minor sensation that we are able to use citral to replicate lavender or mint by means of a simple chemical transformation,” says Wolfgang Krause, PhD, New Business Development & Technical Marketing Aroma Ingredients at BASF. The synthetically produced odorant citral, which is the core product among the company’s own scents, proves to be extremely versatile here. It is not only an important component of violet, lemon, and rose scents, but is also a raw material for vitamin A, vitamin E and carotenoids.

One for all

Citral contains 10 carbon atoms and one oxygen atom. If the molecular structure is changed only minimally, however, this can result in linalool, which smells like lavender, or geraniol, which is responsible for a rose scent. What creates the subtle distinction is the respective position of the oxygen. This may sound trivial, but for chemists or perfumers it is an incredible operation. Like a key that has an edge added or removed, the molecules attach themselves to different olfactory receptors in the human nose, where they create the scent of lavender or lemongrass.

Even the best perfumer cannot distinguish between what we create and the natural original.”

The main plant in Ludwigshafen has been producing this sought-after all-rounder at a newly developed facility since 2004, with a yearly capacity of several tens of thousands of metric tons. The perfume and cosmetics industry is eager to get its hands on the facility’s creative reconstructions of nature. “Synthesis is currently the only way of producing the necessary quantities at a competitive price,” Krause explains.

For centuries, perfumers could rely only on natural fragrances, some extremely rare. The age of synthetic fragrances only began with the production of vanillin in 1874 and musk in 1888. BASF got into the production of fragrances in the 1930s with phenylethyl alcohol, a nature-identical component of rose oil that smells of rose leaves.

Out of about 3,000 known fragrances worldwide that can be synthetically made, the company now has about 100 in its portfolio – the ones that are commercially viable to produce. Usually, a fragrance is required in such small quantities that synthesis, although it may be technically feasible, is not worthwhile, and it is therefore better to rely on the natural substance.

Scents stimulate the brain

Our nose has some 400 different olfactory receptors. It is said that humans can identify more than a trillion different smells. Science now knows precisely how they work. “Smells very clearly stimulate brain activity,” explains Professor Thomas Hummel, who leads the interdisciplinary center for smell and taste at Technische Universität Dresden, Germany. And unlike other senses, olfactory information remains largely uncensored in the brain.

The signals land almost unfiltered in the limbic system, one of the oldest and most primitive areas of the brain, and are stored in our memory along with our emotions.”

He adds that sight and touch, on the other hand, take a detour and first cross the thalamus, which acts as a filter. Fragrances can thus stimulate long-term memory. Even decades later, they still evoke strong feelings in us. Our brain stores olfactory sensory impressions and, as soon as we smell a particular scent, it brings back long-forgotten memories. How good or bad something smells depends very much on the situation in which we noticed the smell for the first time.

However, it is not only the brain that is affected, but also the intestine, which has its own olfactory receptors. These react to scent molecules in food and release the neurotransmitter serotonin, which sets the digestion in motion. Smells also have a surprisingly positive effect on the body through breathing, when the smell is absorbed into the blood via the lungs. In one study, Hummel and his research team found that smells can even improve human cognitive skills. For three months, one group of test participants aged between 50 and 84 had to solve sudoku puzzles daily, while another group had pleasant scents wafted over them. At the end of the test, the puzzle solvers showed no significant cognitive changes, but the participants who had been in contact with fragrances were able to express themselves better and felt an average of six years younger than before the test. Hummel therefore offers this advice: “Our sense of smell declines with age. The best precaution against this progressive loss seems to be to sniff four or more different smells every day – this will keep both your nose and your mind equally fit.”

How well can humans smell?

Keen noses at BASF

An olfactory bulb as a measuring instrument – BASF’s environmental monitoring center has 21 employees at work, not least in order to check on the air around Ludwigshafen, Germany. They use their trained noses to identify smells.

60 40 40

This telephone number is well known in Ludwigshafen. If a local resident is worried about an unusual smell, one of BASF’s environmental monitoring team promptly sets off to the scene with an environmental monitoring vehicle to see what is happening. The team is responsible for monitoring air, water, and noise around the Ludwigshafen site. That includes having veritable supernoses to check the air for smells.

Measuring by nose

Jürgen Huppert is one of 21 supernoses who work around the clock in shifts to monitor the plant. “The nose is one of our most important measuring instruments,” Huppert says. “It detects traces of chemical substances with lightning speed.” During the daily monitoring expeditions outside the plant premises, the sense of smell is initially the first thing that matters, although the measuring instruments in the vehicle are not irrelevant. They are able to identify about 150 individual substances in a very short space of time.

Team

The team is composed of highly qualified laboratory staff and technicians – some of whom have several decades’ experience in professionally using their noses. They undergo regular training to hone their skills by exposing their sensitive noses to a very wide range of odorants, such as benzaldehyde and citral, from a library of smells containing about 60 individual substances.

Origin

The idea for the environmental monitoring center came about after a major warehouse fire some 40 years ago. The idea was to give the public a 24-hour point of contact to report any observations. In addition to the four environmental monitoring vehicles, five measuring points capture the most important air values, such as nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, sulfur dioxide, organic carbon, carbon monoxide, and ozone. Ten rotating cameras observe the site and adjacent areas, and 10 stations measure noise pollution.