The source of progress

Innovations are a driving force and essential to advancement. But what is the story behind them? And how can innovations be fostered? Our feature explores scientific findings, takes a look at how BASF is using new methods to cultivate a spirit of innovation during the celebration of its 150th anniversary, and observes researchers as they make breakthroughs.

Vital, but hard to pin down

Progress in business, science, art and society is only possible if we innovate – if we successfully transform new ideas into better technologies, products, processes and services. That is why businesses, governments and other organizations around the world invest billions of dollars in R&D every year. According to a report by management consultant PwC, last year the top 1,000 companies in terms of R&D spent over €540 billion ($600 billion), representing around 40% of the world’s total R&D spending.

It’s not just about money

For those that get it right, all this effort pays off handsomely. Investors are willing to pay a premium for the stock of companies like Apple and Google, or for start-ups they believe have significant innovation potential. But innovation has proved frustratingly hard for companies to deliver consistently. It certainly isn’t just about the money – after ten years of research PwC has found no direct correlation between an organization’s R&D expenditure and its ability to innovate. Nor is it about formal processes. Companies and academics have postulated a range of models to describe the way from an idea or identified need to a finished innovation, but none has mapped a sure-fire route to success. So how do we nurture this vital but elusive element? Several new approaches are emerging.

“Leading companies are asking themselves how to connect the best people inside with the best people outside.“

Dr. Ellen Enkel, Professor of Innovation Management at Zeppelin University, Friedrichshafen, Germany

Not just more ideas – better ones

In recent years, many organizations have recognized that big R&D budgets do not necessarily turn into profitable innovations. In part, that is due to what Harvard Professor Clayton Christensen terms “The Innovator’s dilemma”. In his 1997 book of the same name, Christensen argued that successful firms inevitably focus their R&D efforts on meeting their customer’s current, stated needs. As a result, they become vulnerable to competitors who introduce “disruptive innovations” that meet customer’s unstated or future needs, use radically different technologies, or serve entirely new customer groups.

Connecting people

In an effort to better prepare for disruption, many organizations are now attempting to widen their search for new ideas. “No matter how big a company is, they will never have all the bright people or all the good ideas,” says Dr. Ellen Enkel, Professor of Innovation Management at Zeppelin University, Friedrichshafen, Germany. “So now leading companies are asking themselves how to connect the best people inside with the best people outside.” To facilitate this ‘open innovation’, as it has become known, companies develop much closer partnerships with suppliers or industry partners, and search universities and start-ups for teams and individuals with bright ideas. They encourage customers, both current and potential, to participate in the innovation processes. And they run competitions, internally and externally to look for new ideas and new solutions to tough problems.

“Any truly radical innovation is going to be disruptive.“

Ashley Hall, PhD, Professor of Design Innovation at the Royal College of Art in London, England

Playing with new ideas

Sometimes the biggest barrier to innovation is the need to destroy the old to make way for the new. Significant innovations upset the established order, often putting long-standing roles, skills or institutions at risk. “Any truly radical innovation is going to be disruptive,” says Ashley Hall, PhD and Professor of Design Innovation at the Royal College of Art in London, England. “And that means it’s going to threaten somebody.”

Innovation through play

It is a point echoed by Henrik Sproedt, Assistant Professor for Innovation Practice at the University of Southern Denmark. “Sometimes people only raise their creativity to the highest level in order to prevent change,” he says. That isn’t just a corporate phenomenon; the history of innovation is also one of resistance to change, from the “sabotage” of weaving machinery by angry workers in the industrial revolution to more recent concerns over some new technologies such as genetic engineering. Sproedt’s research has led him to question many of the ways in which companies manage innovation. “A lot of organizations use a Stage Gate® review process to reduce risk,” he says, but to do that, “someone has to determine the assessment criteria.” But true innovation, he says, is too “complex and chaotic” to fit neatly into such formal evaluation systems. Hall agrees, suggesting that companies could learn much from the way designers work. “Designers tend not to project the answer with the question,” says Hall. “They wander and experiment and are willing to take new directions as they emerge.” In fact, according to Sproedt, innovative activity should look less like work and more like play. “It’s the most natural way for humans to grasp novelty, because in play you take away the fear of failure that limits creativity.”

“Innovative activity should look less like work and more like play. It’s the most natural way for humans to grasp novelty, because in play you take away the fear of failure that limits creativity.“

Henrik Sproedt, Assistant Professor for Innovation Practice at the University of Southern Denmark

Creating an open, innovative culture

So how do companies encourage and foster innovation? Agreement is emerging that it is the culture of a company that is decisive. “There is no satisfactory measure of innova- tiveness today,” says Ellen Enkel, “but if I were to create one, I would want to measure two things: How willing are my employees to accept change, and how well connected is my organization with the outside world?” Sproedt suggests that many companies need to facilitate openness inside their organization as well as outside it. “You need to get all your stakeholders together early to give them time to develop a shared language and a shared understanding,” he says. But even so, he admits, this can be hard for people to do, since the need to accept ideas and approaches from right across the company can cause them to question their own professional identities.

Anybody can engage

But even potentially uncomfortable new working arrangements and relationships can be a catalyst for innovation. “Innovation tends to happen between things, and the more challenging those spaces are, the better,” says Hall. He also highlights one of the most important realizations of recent years: “A great thing about innovation is that it isn’t owned by any one part of the organization – anybody can engage with it.”

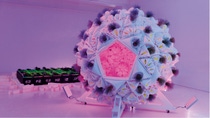

Joining forces to forge new ideas

Developing ideas and concepts to shape the future: To celebrate its 150th anniversary, BASF is creating space for innovative ideas. Creator Space™ is all about creative cooperation between employees, customers, scientists and other groups. To facilitate this, numerous co-creation activities on a global and regional scale are being initiated in various formats, such as jamming sessions, idea contests and open innovation challenges.