Who we are

The explosion of 1943

On July 29, 1943, an explosion rocked the premises of the then I.G. Farben site in Ludwigshafen. Some 64 people lost their lives; hundreds were injured. However, little information survives about the tragedy: State-ordered secrecy during the Second World War demanded that no information be made public. Subsequent bombardments of Ludwigshafen also played a part in shifting attention away from the tragic explosion. Of course, this makes searching for information on the causes of the explosion and the victims that much more difficult. Equally, little was known about the forced laborers who fell victim to the explosion for many decades.

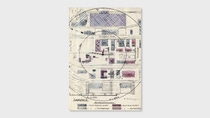

A look at the then I.G. Farben plant before and after the explosion. The building housing the aluminum chloride plant reveals the extent of the destruction caused by the explosion in 1943.

Immediate impressions

The experts charged with determining the cause of the incident not only inspected the site of the disaster in 1943, but also talked to eyewitnesses. On August 2, 1943, a call went out to the employees in every department and plant run by I.G. Farben in Ludwigshafen to come forward with relevant observations and information. Looking back, the archived reports of eyewitnesses provide a vivid and realistic rundown of events and the consequences of the explosion.

Tank car “Mainz 514 442”

July 29, 1943 was a hot day in Ludwigshafen am Rhein. A shunting train comprised of several tank cars and coal wagons was parked in the heat to the south of the plant operated by the former I.G. Farben. The “Mainz 514 442” tank car was fifth in line. It had been filled with a liquid butadiene-butylene mixture four days earlier. At approximately 5:53 p.m., a severe explosion rocked the site, followed by a large fire.

The site plan of the Chemisch-Technische Reichsanstalt (Imperial Chemical-Technical Institute), which participated in the incident investigation, also shows the shunting train from which the explosion originated. The fifth tank car, known as “Mainz 514 442,” (see marking, center) is regarded as the cause of the explosion. (Editor’s note: The map does not show the compass directions accurately.)

The destruction was immense. The area of the Ludwigshafen site, then located between Bunastraße to the north, Styrolstraße to the south, Anilinfabrikstraße to the east and Diaminstraße to the west, was the hardest hit.

The destruction was immense: Numerous buildings, production facilities and warehouse stocks were completely destroyed. Some 64 people were killed, while a further 526 were injured. In October 1943, the Chemisch-Technische Reichsanstalt, a predecessor to today’s Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing (Bundesanstalt für Materialforschung und -prüfung, or BAM), issued the following statement: “Based on the available literature, this is the most devastating explosion caused by a tank car filled with liquefied gas.”

Experts and sabotage

The expert opinion presented by the Chemisch-Technische Reichsanstalt on October 14, 1943 determined a connection between the high temperatures during the day and the (presumably) overfilled tank car “Mainz 514 442.” The theory that the tank car must have been the origin of the explosion was supported by, among other things, photographs of the site of the incident. The burst tank car is documented in the above excerpt, which shows its location on the site premises.

Shortly after the explosion, the site management commissioned internal and external experts to investigate the causes of the explosion. Representatives from the employers’ liability insurance association and the Chemisch-Technische Reichsanstalt were on-site. It did not take long to identify tank car “Mainz 514 442” as the cause of the incident – “with the greatest probability.” Germany’s secret police, the Gestapo, also became involved. They primarily focused on the suspicion that an “act of sabotage” triggered the explosion.

According to the sources, however, all indications supported a different hypothesis: an overfilling of the tank car during high outdoor temperatures. Despite this, the expert opinions did not deliver an unambiguous finding. The report from the employers’ liability insurance association for the chemical industry stated that it was not possible to provide a “complete chain of evidence.”

„Manufacturing at all costs“

Buna was a synthetic rubber with many different applications. The word mark Buna, protected for I.G. Farben, represented the starting materials for rubber synthesis: butadiene (Bu) and sodium (Na). The first Buna plant went on stream in 1937.

The synthetic rubber was used in place of natural rubber, which had to be imported from abroad. The Nazi regime subsidized the domestic rubber industry on a grand scale, with I.G. Farben being the main beneficiary. The objective was to increase domestic production in order to eliminate the dependency on imports.

During the Second World War, the synthetic rubber Buna was primarily intended to meet the rubber requirements of the German armed forces (Wehrmacht). Buna was needed on the front line, among other things in the form of tires. Hence, Buna production was of strategic importance to the war effort.

On July 29, 1943, tank car “Mainz 514 442” contained a liquefied butadiene-butylene mixture which was destined for Buna production. I.G. Farben’s third Buna plant at the Ludwigshafen site commenced operations in April 1943. As the production of synthetic rubber was important to the war effort, the plant was under pressure. As a result, the final stages of the Buna production process were put into operation even though construction of the upstream plant sections – such as distillation – was not finished.

Until the new butadiene distillation facility at Lu 166 was complete, the butadiene-butylene mixture generated during polymerization at building Lu 193 was cleaned in Lu 392. From there, the distilled butadiene was fed back to polymerization at building Lu 193. The associated tank car transport between Lu 193 and Lu 392 was a temporary solution also used in the summer of 1943.

In his internal report of November 1943, Director Dr. Wilhelm Pfannmüller, who was responsible for investigating the incident, not only described its course and possible causes. The contemporary background also came to light, as he pointed out the acute pressure during the war to achieve large production quantities of synthetic rubber.

“Should (...) a discussion arise as to who or what is to blame, it should be clear to everyone that we are not living in peaceful times; rather (...) we are at the home front where turbulent events can occur, such as in this case, and we were told to manufacture Buna for the Eastern Front at all costs!”

A tolerated breach?

The public prosecutor’s office ceased its investigations into a determination of guilt in November 1943. A look at the historical sources shows that both the company and the authorities tolerated a breach of the Technische Grundsätze der Druckgasverordnung (Technical Principles of the Pressure Vessels Ordinance) when it came to filling tank cars at this time. Indeed, the tanks were not weighed during filling, but rather only after they were filled. The obligatory rail weigh-scale at filling station Lu 193, so the argument goes, did in fact not exist due to procurement bottlenecks during the war.

This explains why tank car “Mainz 514 442” was only weighed after filling had been completed on July 25, 1943; its weighing card was evaluated on August 3, 1943 following the explosion. The card reveals that the weight of the tank car exceeded the then permissible weight by 15 percent.

Overfilling and high temperatures

The term “tank car explosion” is frequently used. Today, however, this term would not be deemed correct for the incident on July 29, 1943: The tank car itself could not have exploded, as no explosion crater was found. The conclusion: Gases or vapors must have triggered the explosion.

The explosion of July 29, 1943 originated at tank car “Mainz 514 442,” identified in red in the photo. The tank car was presumably overfilled with a butadiene mixture, causing the tank to tear open due to the increasing internal pressure.

Although the report from the employers’ liability insurance association for the chemical industry stated that a “complete chain of evidence” was not possible, both site director Pfannmüller and external experts assumed that the explosion was caused by overfilling. The following sequence of events was deemed plausible at the time: The high outdoor temperatures on July 29, 1943 heated up the tank car dramatically, causing the butadiene mixture to expand. As a result, the pressure inside the tank car increased and the tank car ultimately burst. The gas mixture leaked from the tank car in liquid form, evaporated outside the tank, mixed with air and was exposed to an ignition source.

“The gas cushion in the tank car was insufficient”

Dr. Vera Hoferichter, head of BASF Gas Phase Explosions & Ignition Sources, takes a contemporary look at the reasons behind the gas cloud explosion in 1943. She is convinced that if tank car “Mainz 514 442” were to be evaluated using current specifications and findings, it would clearly be classified as being overfilled.