“We are unwilling victims of a global machinery based on manipulation and exploitation.”

Carl Tillessen,

Consumerism expert

Media

In all likelihood, while reading this article, you are wearing clothes – just as people have been doing for around 170,000 years. At first, people used leaves and fur to cover their bodies. Nowadays, clothing is like our second skin. It shows who we are, or want to be. In 2022 alone, the average U.S. citizen purchased around 68 pieces of clothing, according to the American Apparel and Footwear Association. And the numbers are similar in other industrialized nations. But why do we keep buying, even when we have enough?

“Shopping activates biochemical processes in our brain similar to those triggered by taking cocaine or falling in love,” explains Carl Tillessen, chief analyst at the German Fashion Institute in Cologne and author of a bestselling book about consumerism. It is completely irrelevant whether we need the item or not; it’s all about the feeling when we buy it. “Fashion in particular offers a quick and easy way to satisfy our ostensible needs, because it attracts us with constantly changing trends.”

While a new outfit can brighten your mood, there is often a dark side to garment production. The fashion industry is responsible for about 10 percent of all CO2 emissions – more than international aviation and maritime transport combined. Not to mention water pollution and mountains of discarded textiles, a consequence of cheaply produced “fast fashion” that constantly launches new collections. Tillessen urges us to become more aware of what we really need and the conditions under which our clothing is produced. For workers, these conditions are often catastrophic, as disasters like the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory in Bangladesh in 2013 show. “That is just one of many dreadful examples of the poor working conditions in low-income countries, where child labor is common despite numerous national and international efforts.”

Assessing the sustainability of fashion purchases is not easy. Sustainability is a multidimensional term encompassing environmental, social and economic components. This article cannot cover all aspects, but it aims to both inform and encourage – because there are promising solutions out there. Innovative technologies, alternative raw materials and new legislation are creating opportunities to reduce the environmental impact of fashion consumption. And we as consumers have influence, too. Let’s start with fibers.

“We are unwilling victims of a global machinery based on manipulation and exploitation.”

Carl Tillessen,

Consumerism expert

It is expected that nearly three-quarters of all textile fibers processed worldwide will be synthetic by 2030, and 85 percent of these will be polyester. It is lightweight, tear-resistant and dries quickly – a brilliant invention to be sure. But synthetic fibers, such as polyester, acrylic and nylon, are not biodegradable and release microplastics. When washed, synthetic garments release around half a million metric tons of microfibers each year that end up in the ocean, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Spanish fashion group Zara Home now offers a detergent that can reduce microfiber shedding by up to 80 percent during a wash cycle. The product, jointly developed by BASF and Zara’s parent company Inditex, has already been launched in Mexico and Europe and is particularly suitable for washing at low temperatures. It protects the fibers, increases the useful life of textiles and lowers the environmental footprint of doing laundry.

Synthetic fibers are not your thing? Then your second skin is probably made of cotton, the second-most commonly used fiber. But, like synthetic fibers, cotton does not have an entirely impeccable record. There are many reports about human rights violations on cotton plantations, such as forced labor in Turkmenistan. In addition, cultivating cotton requires many resources, from huge fields to vast amounts of water. For example, it takes 7,500 liters of water to make one pair of jeans and a large part of this is for growing cotton, according to the United Nations. But there is a different way, with sustainably grown cotton. We will come back to this later.

Fibers made of other renewable raw materials can be more resource-efficient. Hemp, for instance, was already being used to produce textiles in China about 6,000 years ago. Compared to cotton, this undemanding plant needs only half as much water and produces 220 percent more fiber. Yet, hemp is still just a niche product in the garment industry. For one thing, it is much more difficult to process than cotton. And because of hemp’s reputation as a “drug plant,” its cultivation was banned in many places, so farmers are often unfamiliar with it. This is not the case in China, a pioneer when it comes to hemp textiles. The country currently produces more than 50 percent of the world’s industrial hemp. Besides hemp, a number of alternative raw materials offer enticing potential.

But whether polyester, cotton or hemp – all thread needs color.

Julian Ellis-Brown

“We were looking for a material that warms without harming the environment or animals.”

When Julian Ellis-Brown speaks, even King Charles III listens. The young CEO and co-founder of the startup Ponda presented the British monarch with a tailor-made stepped vest in summer 2023, explaining the benefits of its sustainable filling, and the “green king” was all ears. The idea for the fluffy filling material called BioPuff® – an alternative to down – came to Ellis-Brown and three of his fellow students during their master’s program in innovation and design technology. They found bulrushes – plants capable of sequestering carbon and recultivating soil. “What drove us was the idea of a design that would actively help saving the planet,” he says. In the lab, the four students developed a method for extracting a soft filler material from the plants’ rough bulbs. For its innovative idea, Ponda has received the Global Change Award, among other honors. Not yet 30 years old, the tireless conservationist is already working on the next new bio-materials together with various research institutes.

Ponda makes materials that benefit the environment.

They produce a vegan alternative to goose down from bulrushes grown by regenerative wetland agriculture.

Our ancestors also liked brightly colored clothing and used substances found in nature to dye their textiles. For example, sea snails from the Muricidae family could be used to make the radiant Tyrian purple dye, which was so precious that it was only available to the elites. Or there was indigo dye – the “blue gold” derived from natural pigments that colored the linen strips used to wrap Egyptian mummies. These days, in the majority of cases, it is synthetic dyes that are used to make our outfits colorful. Dyeing processes not only require a lot of energy and chemicals, but also enormous quantities of water. According to the World Resources Institute, around 5 trillion liters of water are used to dye fabric each year – enough to fill 2 million Olympic-sized swimming pools. One of the consequences is that, according to the U.N., about 20 percent of industrial water pollution worldwide is due to dyeing and textile treatment. It is an open secret that untreated water from dyeing factories is being illegally discharged into rivers.

Dyeing doesn’t just have a negative impact on the environment, it is also harmful to the health of people who work in the sector. One example is tanning and coloring leather, which uses chromium salts, alkaline solutions and dyes. People who work in leather processing in low-income countries often have no or only rudimentary protective gear, so they come into direct contact with these substances – often with severe health consequences.

The search for sustainable alternatives means that natural dyes are making a comeback. The Swedish startup Mounid, for example, has developed an algaebased dye. When applied with spray technology, it consumes up to 90 percent less energy and water than conventional dyeing methods. Because of the fine atomization, it is usually more precise and requires less dye. In contrast to other natural raw materials, microalgae do not compete for arable land and can be produced quickly in large volumes. But for the time being, it is impossible to produce alternative dyes at the scale needed by the fashion industry.

One thing that is abundantly available is used clothing. Let’s explore what happens – and could happen – with the clothes we no longer use.

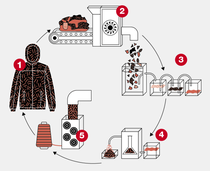

BASF has developed an innovative solution for textile-to-textile recycling.

A chemical recycling process can transform old clothing into loopamid®, a starting material for new polyamide fibers, which can be used to make new 100 percent circular clothing.

Clothing gets sorted and shredded.

The fabric shreds are broken down into their chemical building blocks (depolymerization).

A cleaning process follows, as the material can contain contaminants and by-products. The output: high-purity chemical building blocks (monomers).

The monomers are transformed back into pure polyamide 6 (polymerization), creating a product called loopamid®.

loopamid® is the starting material for new polyamide 6-fibers, which can be used to make new, 100 percent circular clothing.

“What we need is more circular economy,” insists Professor Edwin Keh, CEO of the Hong Kong Research Institute of Textiles and Apparel. “Our garments are often made of synthetic blended fibers that are difficult to recycle.” Until now, sorting for fiber-to-fiber recycling has been complex and expensive.

Although the mechanical separation of fibers is a technically established process, knowing the fiber and mixture composition is important to ensure optimal recycling. However, this is difficult when garment labels are missing, faded or contain incorrect product information. This is where near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy can help. The established method, which already supports material identification in plastics recycling, utilizes near-infrared light to make molecules vibrate. The vibrations, which vary from material to material, are detected by a sensor and compared with a database so that the result indicating the textile type is available in a matter of seconds. BASF’s subsidiary trinamiX has developed a compact NIR-based solution for sorting textile waste by composition, which helps keep garments that can no longer be worn in the textile loop. The solution is applied, for example, by Germany-based Soex Group, a global leader in recycling used textiles.

“We need more circular economy.”

Edwin Keh,

CEO Hong Kong Research

Institute of Textiles and Apparel

Chemical recycling can bring us closer to a circular economy by turning used plastic into clothing. In chemical recycling, the long plastic polymer chains are broken down into their basic building blocks. “The benefits are less waste, less resource use and less pollution,” says chemist Izzy Manuel. She is an influencer for ethical “dopamine dressing” – a colorful clothing style that aims to lift the spirits – and an influential voice advocating for sustainable fashion in the United Kingdom.

Sustainable fibers and dyes. This sounds good and feels good. But how can we tell how our new favorite T-shirt stacks up?

Danit Peleg

“Imagine a world where we buy digital files of clothes, download them and print them at home.”

“Imagine” is written in bright red letters on Danit Peleg’s 3D-printed jacket. Its creator herself sparkles with imagination. In thousands of hours of tinkering in her Tel Aviv studio, the Israeli has inspired the fashion industry. A graduate of Shenkar College of Engineering and Design, Peleg was the first in the world to create her graduation collection at home using standard 3D printers – and she was the first to offer such clothes in her own online shop. “I enjoy experimenting with new materials, and I am interested in pushing the boundaries of printing techniques and software developments to make fashion fit for the future,” she says. The 35-year-old’s vision: In the future, consumers will buy digital files to print and personalize their clothes themselves using affordable 3D printers. “That way, there will be nearly no waste, and the supply chain will be circular and hopefully radically cleaner,” she says. The BBC chose Peleg as one of its 100 Women for 2019.

Imagine you could print your own clothes at home!

Young designers such as Danit Peleg are leading fashion into this future with their 3D-printed collections.

BASF’s #Seed2Sew project in Greece shows how this can work in Europe’s largest cotton-producing country. #Seed2Sew 2022 is part of BASF’s Certified Sustainable FiberMax® (CSF) cotton program. CSF promotes the sustainable cultivation of cotton – lower CO2e emissions, less water consumption, and the precise use of crop protection products and fertilizers. In addition, careful soil cultivation, crop rotation, regular soil analyses and drip irrigation protect soils and save water and energy. About 1,600 farmers, three cotton ginning plants and one spinning mill are participating in the program, annually producing about 50,000 to 55,000 bales of cotton.

#Seed2Sew now also addresses the transparency of the cotton supply chain from seed to retail. “We are using blockchain technology to make the cotton supply chain more transparent and traceable,” explains BASF blockchain expert Abhijeet Sharma. A blockchain is a database that stores data in digital blocks chronologically as a data chain. The data chains are stored on different, networked computers that monitor each other. The system is considered particularly transparent and secure, as tampering is quickly spotted. Farmers record their sustainable cultivation activities via a blockchain-supported app.

The data is linked to a scannable QR code on each cotton bale. “In the end, the finished garment can also be tagged with a QR code, so every step can be tracked from the field to the end consumer,” says Sharma. Five farmers, a ginner and a spinner, as well as manufacturing partners, are involved in the blockchain project #Seed2Sew. This is approximately equal to 315 hectares of cotton-producing land that could generate 2,100 lint bales, with the potential to make more than 2.3 million T-shirts.

BASF has set up a similar project in the United States. The e3® Sustainable Cotton Program empowers cotton farmers to showcase their sustainability efforts, and offers brands in the fashion and textile industries access to transparently sourced, sustainably produced cotton.

QR codes are not the only way to get information about our clothes. Textile standards also offer us clues. If you look at the tag inside your clothes, do you see a label with a seal? You have made a sustainable purchase if you find one showing a white shirt on a green background. The GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard) seal is one of the strictest textile standards worldwide. It considers environmental and social criteria throughout the entire supply chain. Another very strict environmental standard is the IVN Best certification from the International Association of Natural Textiles (IVN e.V.).

IVN covers the supply chain for natural fibers, from organic farming to the final product. But not all certifications are this comprehensive. The Oeko-Tex® Standard 100, for example, is one of the world’s best-known labels, but it only tests for harmful substances in the final product. It does not provide any information about the production or environmental impact of a garment. So it’s definitely worth checking closely which certification labels are on your clothes. But these standards alone are not enough.

In this field near Komotini, Greece, cotton takes center stage. It is sustainably produced as part of BASF’s CSF program.

Every step can be traced via blockchain – from the field to the shop.

“We need government leadership to make the industry fairer by law,” says British social entrepreneur Safia Minney. What are governments around the world doing to make tailor-made fashion laws?

Many fashion companies have already recognized the need to act. One pioneer when it comes to sustainability is U.S. sportswear manufacturer Patagonia, which received the U.N.’s Champion of the Earth Award for its commitment. The company has been using recycled plastics since the 1990s, and launched a recycling program for its own clothing in 2005. In addition, it has established a social responsibility program for its supply chains. Many other producers have now done the same.

Advertising sustainable collections is now basically part of the standard repertoire of fashion labels. About 100 of these companies have signed the United Nations’ Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action. As signatories, they commit to reducing their greenhouse gas emissions by 50 percent by 2030, as compared to 2019 levels. However, the environmental organization Stand.earth studied 10 of these companies and found that Levi Strauss & Co. was the only one likely to reach this target. “We need to bring about a cultural change among fashion companies and redesign the industry that it fits our planet and becomes fairer,” says Safia Minney. She is the founder of the ecological fashion label People Tree. It is considered the first label in the clothing industry with a completely sustainable supply chain, including strict certification – such as the GOTS seal.

“We need to bring about a cultural change among fashion companies.”

Safia Minney,

Founder of People Tree

The European Union wants to introduce a directive on corporate sustainability due diligence, which will apply to companies in all sectors, including the apparel industry. This law would oblige larger E.U.-based companies and foreign companies with a certain level of sales in the E.U. to protect human rights and the environment throughout their global supply chains. Moreover, the E.U. also wants to promote the circular economy. As a key component of its Green Deal, Brussels is about to adopt an Ecodesign regulation. The final discussions between the European Commission, Parliament and Council are under way. Among other things, this legislation would introduce an E.U.-wide ban on the destruction of brandnew textiles and shoes that are unsold or returned to the store. In general, its aim is to ensure clothing becomes more durable, easily recyclable and environmentally friendly by 2030.

Policymakers in other parts of the world are also taking action. In the United States, a new legislative proposal called the Fashion Act has been introduced in the state of New York. One goal of the law is to improve working conditions. At the same time, companies that want to sell their goods in New York state will be obligated to reduce their emissions in line with the Paris Agreement.

Jessica Chang

“Upcycling means to reuse materials that previously ended up as waste and give it a new life.”

Whether it’s unsold textiles or secondhand clothing, Jessica Chang gives it all a second chance. “Just as fashion trends are recycled, worn clothing can be too, so it doesn’t end up in the trash,” she says. The young designer grew up in Hong Kong and studied fashion design in New York. With her upcycling approach and reuse of textile waste, she is impressing the fashion world. Her collection “The Wall” won the Redress Design Award 2021, one of the world’s biggest competitions for sustainable design. The presented pieces are extra durable thanks to breathable openings, which ensure less sweating and less need to wash the clothes. Although Jessica has demonstrated the potential of discarded textiles, she herself avoids rejecting items wherever possible. “I am currently working on my fashion label PCES, which focuses on zero-waste patterns and recycled textiles to avoid any textile waste,” she says.

Designer Jessica Chang’s collections feature recycled textiles and zero-waste patterns.

“It’s the lifestyles of people in the North that are responsible for global warming, yet people in the Global South are bearing the brunt of climate and ecological collapse, and simultaneously fashion’s buying practices and trade terms are getting worse. We need to face into the responsibility that is calling all business leaders,” says Minney, who is also a founding member of the global network Fashion Declares. This is primarily concerned with “accelerating change in one of the most environmentally damaging and unfair sectors in the world,” says Minney. As well as publishing informational materials, the initiative offers regular webinars and launched the Regenerative Fashion Conference. “We need more transparency and collaboration among ourselves, we should share best practices and spark industry-wide debates,” the entrepreneur adds. Industry alliances face enormous challenges, as the example of the Partnership for Sustainable Textiles makes clear. It was initiated by the German government in 2014 in response to the Rana Plaza disaster. The Partnership advocates for a socially and environmentally responsible, corruption-free textile and garment industry. In the meantime, some members, such as the Clean Clothes Campaign, have left the initiative, saying the alliance has not improved working conditions in the global fashion supply chain.

Worldwide, policymakers and apparel brands have put sustainable fashion on their agenda. And many young designers have sustainability in their DNA. But to achieve sweeping changes in the industry, consumers will also have to do their part. “People buy more clothes and throw them away faster,” points out Professor Keh. Let’s look at how consumers can contribute.

Isn’t it annoying when jeans look great in the online shop but turn out to be too small, too big or just not right? Returning unwanted purchases is a hassle, and it causes packaging waste and transport-related CO2 emissions. A virtual changing room, such as the one offered by German online retailer Zalando, might help. A customer enters a few parameters into the app, such as their height and weight, to create a personal avatar that can enter the virtual fitting room. Even fashion shows are moving into the digital realm. Labels such as Dolce & Gabbana, Tommy Hilfiger and DKNY sent avatars onto the digital catwalk during Metaverse Fashion Week 2023. This saves fabric because the collections do not have to be physically produced for the show, and avoids CO2 emissions associated with transport and travel. Virtual fashion is nothing new in the gaming sector. Fortnite players, for instance, have long been able to purchase “skins” to deck out their avatars.

Quality over quantity: You can be welldressed with just a small wardrobe of high-quality basics (ideally with a textile certification). A “capsule wardrobe” contains pieces that can be combined with each other to make various outfits for every occasion. One of the first capsule wardrobe collections was released in 1985: US designer Donna Karan’s Seven Easy Pieces – seven items that could be mixed and matched. There are now many such collections on the market.

Getting a hole in one of your capsule basics does not have to mean it’s time to toss the item. Some clothing, such as pieces from U.K. firm WoolOvers, come with matching yarn and buttons to repair the garment. If you don’t have the skills or desire to fix it yourself, repair services are available. Online retailer Zalando, for example, started a pilot project called Care & Repair in 2021 and is now evaluating the program and its next steps. With this online service, customers were able to have their damaged clothing or shoes picked up at home and repaired by local businesses. By the way, in France, clothing repairs are now even subsidized by the government. Starting last October, anyone who takes their damaged apparel to a tailor or shoemaker is eligible to receive a repair bonus.

Or should your old coat be revived like the phoenix from the ashes? With its Renew program, U.S. fashion label Eileen Fisher offers a take-back service for items from its own collection. The clothing gets cleaned and partly upcycled. The company says that since 2009 it has taken back 1.9 million garments, which have been resold or transformed into new designs. This service does not only offer environmental benefits: Customers receive 5 U.S. dollars for each returned item of clothing – no matter what condition it is in. A similar approach is being followed by Swedish fashion label Asket. The company has opened a store in Stockholm, where it offers used and repaired Asket garments and is planning to host upcycling workshops for customers.

“The circular economy is beginning to shape clothing production, and on the consumption side, buying secondhand, rental and repair offer a way to reduce the ecological impact of fashion,” says Safia Minney, who has been buying secondhand fashion and trading clothes since she was 17. Meanwhile, her nieces benefit from the clothes she no longer wears. For those who don’t have an aunt who is a fashion designer: Online platforms such as Rent the Runway offer designer clothing and accessories for rent. More than 140,000 people currently use the U.S. firm’s clothing subscription service. “In our society, we are used to buying lots of clothes on a monthly, weekly or even daily basis. It can be hard to break that habit. To do so, before I make a purchase, I ask myself: Will I really wear this? Am I buying it just because it’s a bargain or because I’m in a buying mood right now?” The maxim when it comes to your own wardrobe should be: Slow down! Be intentional and inform yourself before buying something new. Buy fewer items but carefully chosen ones of good (recycled) quality. And, wherever possible, trade or upcycle. Our clothing choices determine how much responsibility we take on for people and our planet.