60 %

of the world’s population lives in Asia on around one-third of the world’s land mass.

Focus

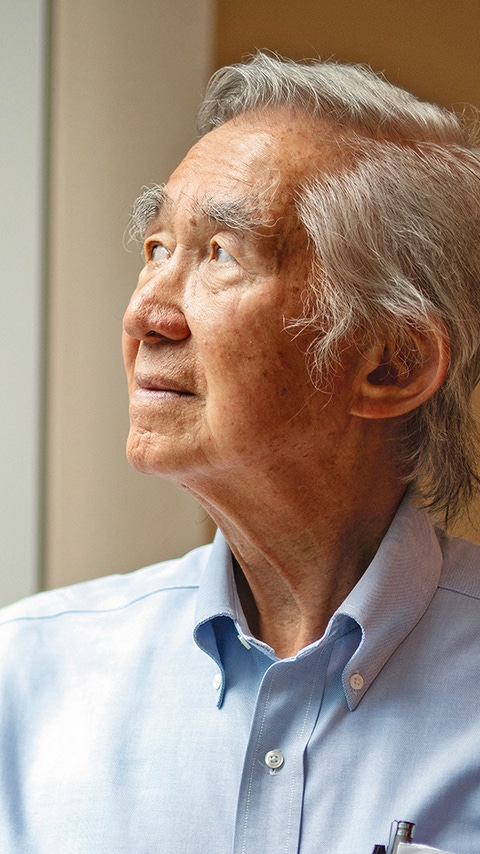

Interview with Dr. Liu Thai Ker

Priopćenja i novosti

Dr. Liu Thai Ker, Singapore’s former chief city planner, transformed the island state from a collection of slums into one of the world’s most liveable megacities. Here, he explains what really counts.

Liu Thai Ker: When I started work as an urban planner in Singapore in 1969, the city had a population of 1.6 million. Today its population is nearly 6 million. There was a sketchy but well-conceived concept plan prepared in 1971. My role was to fill in the details of the new town plans in line with the broad framework. The plans we laid down over those decades have stood us in good stead, despite our rapid growth. The key is that we subdivided the city into smaller urban cells. In this way, the population of 6 million is broken down into smaller and smaller communities until you feel as though you are living in a high-rise village.

We divided the city into five regions each of 1.1 million people. Each region is like a small city. Each region is then divided into new towns of 200,000 to 300,000 people. You can live your whole life in a town of that size: be born there, go to school and work there and, if you need to, go to hospital. The towns are divided into neighborhoods, defined as an area you can walk to. We then divide these neighborhoods into precincts with an area of 2.5 to 4 hectares each. Sociologists say this is small enough for people to develop an emotional tie to the land. With less than a thousand families in a precinct, people know each other and develop community cohesion like those in traditional villages.

Between 1960 and 1985 people were being moved into public housing for the first time in massive numbers. They were strangers to each other, many from different social-economic strata and ethnic backgrounds. Creating a sense of belonging was therefore very important. The precincts meant that people soon got to know each other and began treating each other as friends, rather than strangers. That is one reason why Singapore is a safe place today.

In Asia many cities have a population of over 10 million; Shanghai’s population is more than the whole of Australia. My advice for those cities was not to treat each as one city but as a constellation of smaller cities, independent from each other and yet related, with facilities distributed to each of them. This means a person can walk to their neighbourhood center to get what they need; they don’t need to drive. That cuts down travel time, uses less fuel and improves air quality. In China, I have planned three cities with populations of 12 million each on this basis. Urban planning affects human behavior – if we plan well, that will encourage behavior that saves time and energy, and improves the lives of citizens.

This issue is more acute in Asia than in the West. Asia has 60 percent of the world’s population living on around one-third of the world’s land mass. We therefore have no choice but to consider high-density living, but we also have to create good, liveable environments. No government, no matter how powerful, can stop people moving to a city that is growing well. The job of a planner, therefore, is not to determine what population size the land can bear, but to project on a long-term basis the likely population size that the city may grow to and consider the floor areas required equivalent to those of a highly developed city, for all the daily activities of each citizen. Only then can the planner allocate the various types of land use and sizes required within the land constraints.

60 %

of the world’s population lives in Asia on around one-third of the world’s land mass.

When I came back to Singapore in 1969, the city was desperately poor, but I had to plan new towns with proper housing for the lower income group. I believed that we had to try to plan our housing and facilities to match, as closely as possible, the first world standard. So, I took a study of the floor area occupied by people in America and used that as a guide. Even in a third world country you should plan for first world standards. It is too expensive to go through the various steps of transition and upgrading, demolishing substandard buildings and replacing them with better ones.

An open corridor in an apartment block in Ang Mo Kio, one of Liu’s planned towns in Singapore. Public transport is in close proximity.

Good long-term planning is the starting-point. When I plan for cities now, I plan for 2070, because that is when the global population is predicted to peak. We plan for the whole area and then implement the plan in phases, so that there is continuous expansion, rather than leapfrogging. This is what we did in Singapore. Once the first phase of infrastructure was laid, people moved in and we started collecting taxes – so were able to develop a city without borrowing money from the World Bank, despite starting as a very poor country. You need intelligent planning plus intelligent administration for a good urban environment.

A planner or a government cannot know everything. You need constructive feedback from citizens. Working in public housing, we not only planned and supervised construction, but also managed completed buildings. The beauty of this is we got lots of complaints, so we organized research units to sort out the ones highlighting flaws we had made in the design and planning. Every month we plowed back the gems of these complaints into new urban planning and design. This process continued for 20 years. You can imagine how much I learned.

Reclamation: How cities can win back and find new uses for lost or residual urban spaces.

To me a smart city is like the vitamin to a body. The job of a planner is to make sure the body is healthy. That requires careful, intelligent planning. Only on that basis can you then take on vitamins to make the city stronger. The vitamin is the smart part of it, the technology. My biggest fear is that people think that technology can solve urban problems. It can’t. Urban needs must be met through intelligent planning and design, which requires real hard work. The ideal situation is to combine smart technology with good planning, but there are not yet many good examples of that in the world.

As a planner you have a very sacred responsibility to the people in your city.”

The goal of a city planner is guided by five E’s. You need Ecology so that you do not contribute to global warming. You need Education, because you want a strong work force. You need a good Environment for people to live happily. Then you will get Economic growth because you will attract investment and talent to the city. If you achieve these first four E’s, the citizens of that city gain Esteem, and to me, that must be the ultimate goal of an urban planner. Just focusing on environment and ecology is too low a goal. As a planner you have a very sacred responsibility to the people in your city and you have to do your level best to achieve that.

The strong emphasis on technology as a solution for urban problems worries me a lot. We must place more emphasis on intelligently planning a city. Architects and planners tend to think of themselves as imposing their creative ideas on the land. I don’t think like that. I consider myself a servant of the land and its people. If planners, politicians and architects see themselves in this way, then maybe the world will have better cities.

Some 15.1 million people live in Istanbul today. This makes the city on the Bosporus the most populous in Turkey – an exciting metropolis in which the changes of the past decades can be seen clearly in the photo comparison. Compared to 1927, when the population was about 680,000, it is 21 times as big today. This picture slider takes you on a journey through time to some striking locations in the Turkish metropolis.