Creating Chemistry Magazine

Boxing clever

These days, nearly as much research and development goes into how we package our food as goes into the food itself. Innovations and high-tech solutions mean that the cartons, films and bottles ensure that the food is kept fresh and safe, helping food production to become more efficient and safe.

In Austin, Texas, there is a supermarket where customers are advised not to come empty handed to do their weekly shopping: fabric bags are the order of the day. Shoppers who fail to bring these must buy compostable containers to take home their purchases of fruit and vegetables, which are largely locally grown. Known as the first precycling supermarket in the United States, it does not offer any packaging at all.

What may work on a small scale, however, is simply inconceivable at a larger level, with food packaging now an essential part of our everyday lives. “Packaging is key when it comes to protecting our products, guaranteeing our high quality standards, preventing food waste and informing consumers,” says Dr. Anne Roulin, Global Head of Packaging and Design at Swiss food conglomerate Nestlé. There are many reasons for the growing need for food packaging. More than half of the world’s population lives in cities, where there are few options for growing food independently. The planet’s 3.5 billion city-dwellers thus buy their products outside of the home – and they usually come packaged. In addition, the rising number of single-person households, which prefer smaller portion sizes, and the growing trend of eating on the move between appointments are giving rise to an increasing amount of packaged food.

1.3 billion

The number of metric tons of food production – around one-third of the total – lost or wasted every year worldwide.

95–115kg

The amount of edible food per person that is lost or wasted each year in industrialized countries.

Freshness is imperative

The demands made of packaging are high. Guaranteeing freshness and hygiene is a particular challenge, as foods must often cover great distances when travelling from their place of origin to supermarket shelves. Further time passes before they find their way into a shopping basket, and then again before they ultimately end up on the dining room table. Highly developed technology ensures packaging can keep products impeccably fresh and hygienic. A quick glance in the refrigerated section shows the complexity of what is involved – the packaging for cheese and sausages, for example, is made of a wide range of plastics. The differing characteristics of these composite materials are combined to ensure the packaging is ideally suited to the food. The base of the packaging, for example, can be produced to have different characteristics than the lid or wrapping film.

Hard-wearing composites made of various materials are also well suited for use in what is known as Modified Atmosphere Packaging or MAP. With this technology, the air surrounding an edible product is replaced with a protective atmosphere specially tailored to the food. One example is a mixture of nitrogen and carbon dioxide. These slow-reacting gases replace oxygen, and slow the growth of germs, all without using any preservatives. To ensure the solution works properly, the packaging material must form an effective gas barrier. Otherwise, the valuable protective atmosphere would quickly be lost.

In Japan, the development of sophisticated packaging systems is also driven by regional eating preferences. Japanese consumers react very negatively to packaging that no longer appears perfectly intact from the outside; even harmless creases or folds in packets can cause perfectly fine food to be left on the supermarket shelf. Fish and seafood are often on the menu, and it is particularly important that they are kept fresh and protected against spoiling. It is popular to package foods accompanied by small sachets filled with substances that bind moisture, such as silica gel and starch polymers. “For Japanese consumers, the presence of sachets indicates that the product is very well protected,” explains Sven Sängerlaub from the Fraunhofer Institute for Process Engineering and Packaging (IVV). In contrast, many Europeans view such tiny sachets of moisture-binders with suspicion, and their presence inside a package can prompt skepticism about the food it contains.

How can consumers accurately assess the condition of products? Uncertainty in this area often leads to waste: “Too many consumers see the best before date as an absolute cut-off point, although many foods can still be eaten after this time,” explains psychologist Stephan Grünewald, from rheingold, a German market and media analysis institute. Every year, in industrialized countries, 95 to 115 kilograms of perfectly good food is lost or wasted by each person, according to a study by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

In years to come, ‘intelligent’ or ‘active’ packaging could help reduce food waste. This is a response to experts’ efforts around the world to come up with new ways to inform consumers about the perishability of food and to protect against spoiling. The new systems could display the state of a product, and at the same time increase its lifespan with oxygen absorbers or special acids. As an example, American firm Sonoco is currently developing packaging with integrated microchips that collect information about the condition of a product, such as moisture and temperature. It raises the alarm when preprogrammed thresholds are exceeded or fall below target. “In the future, I expect to see a shift in business models towards direct contact with consumers,” predicts Dr. Anne Roulin from Nestlé.

Environmental awareness

Alongside freshness, increasing numbers of consumers want packaging that can be recycled. According to a survey of 6,000 consumers in ten different countries, carried out by Swedish carton manufacturer Tetra Pak, recyclable packaging is one of the public’s key priorities, as it is seen as kinder to the environment.

Consumers and legislative regulators are becoming increasingly concerned with packaging. The aim here is primarily to encourage the efficient use of resources. This trend is particularly noticeable in Europe. In the Netherlands, for example, a tax is applied to packaging manufacturers according to the average CO2 emissions of the materials used – 36 to 57 euro cents per kilogram for aluminum packaging, 6 euro cents for cardboard.

Sustainable packaging can be worthwhile for packaging manufacturers and food companies. In Europe in particular, demand is on the rise for paper and cardboard packaging with environmentally friendly recyclable fibers, which are also cost-effective. In addition, companies are working to come up with solutions that simplify packaging designs so that recycling rates rise.

Biodegradable materials

Recycling is one thing; there is growing demand for renewable materials that are biodegradable too. Drinks cartons or food containers, for instance, can be made of biodegradable plastics formed partly of renewable raw materials. After use they can be disposed of and composted with the rest of the food waste.

Reducing the weight of packaging is another way of protecting the environment while protecting companies’ bottom lines. As well as cutting the CO2 emissions generated during transportation, making packaging lighter can reduce costs too. Corrugated cardboard, frequently used in transport packaging for food, can be reduced in weight with the help of fluid synthetic dry strength agents. These mean that fewer paper fibers are needed to construct the cardboard, without compromising its strength.

Focusing on health

In many countries around the world, the trend towards greater sustainability goes hand-in-hand with an enhanced awareness of personal health. As well as information about the contents, food packaging should also provide details relating to nutrition, calories, and possible allergy triggers.

Potentially dangerous substances are not limited to the food, however – they can also be found at times in the packaging material itself. In 2010, researchers at the Zurich Food Safety Authority in Switzerland found that mineral oil residue contained in cardboard packaging was being transferred to foods. The main source of the problem was deemed to be ink used in newspaper printing, which found its way into the packaging via recycled paper. The residue traces detected also occasionally came from inks used to print the food packaging. These oil residues evaporate at room temperature, and can then be transferred to dry foods, such as pasta, semolina, rice, or cornflakes. This is even possible merely when the transportation packaging of the food contains recycled paper. Certain components of mineral oil are suspected of being carcinogens, according to the World Health Organization’s Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives, and the FAO.

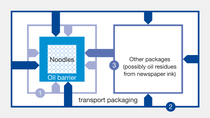

Mineral oil barrier in packaging

Going forward, one way of reducing or even entirely eradicating mineral oil residue in paper and cardboard packaging is to use water-based binders for mineral oil-free printing of newspapers. In addition, food can be protected against the migration of unwanted substances through functional barriers.

Functional barrier solutions are currently available for practically all types of packaging and standard manufacturing processes. In this way, our food is reliably protected from mineral oil and other potentially critical substances.

Over the last few years, research into the best, most secure types of food packaging has made major advances. Guaranteeing safety, providing freshness, and delivering information, our food’s containers are increasingly sophisticated and play an important role in our everyday lives.

The mineral oil barrier protects food

Food packaging is often made of recycled paper fibers. This recycled paper packaging can contain newspaper ink, which researchers have identified as the main source of potentially harmful mineral oil residues in cartons. These oil residues evaporate at room temperature and can thus be transferred to dry foods that contain fats, such as noodles.

Mineral oil residues can migrate from:

- the inner side of contaminated primary packaging

- contaminated outer packaging, for example, corrugated board packaging used to hold products during transportation

- contaminated packages in close proximity, for example, on the supermarket shelf or in delivery trucks