Who we are

A Troubled Chapter in German Industrial History

Reflections on the Founding of IG Farben 100 Years Ago

Aware of the partially incomplete state of research, BASF Corporate History sheds light on selected aspects of the history of the IG Farben sites in Ludwigshafen/Oppau on the 100th anniversary of the merger. It also addresses how BASF’s engagement with the IG Farben chapter has evolved: from silence and suppression to reassessment and the assumption of historical responsibility.

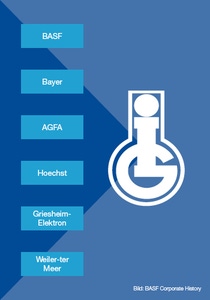

On December 2, 1925, the merger created by far the largest German chemical company, ranking among the five most important corporations in the industry worldwide: IG Farben. The company emerged from the union of BASF with Bayer, Agfa, Hoechst, Griesheim-Elektron, and Weiler-ter Meer. Many innovations—often originating from the former BASF sites in Ludwigshafen/Oppau—are considered scientific and technological milestones. Yet all of this is overshadowed by the company’s profound historical responsibility: Today, the name IG Farben is inseparably linked with the Nazi regime, Auschwitz, and the IG Farben trial. Driven by economic considerations, the company maneuvered itself into close cooperation with the Nazi regime starting in 1933. Through its substitute products, it supported the regime’s policies of autarky and rearmament, ultimately enabling its war of aggression and extermination.

From BASF to Upper Rhine Opperating Group

In April 1925, BASF celebrated its 60th anniversary with a special edition of the company newspaper. By the end of the year, however, BASF no longer existed as an independent entity. Instead, the sites of the founding companies of IG Farben were reorganized into groups known as ‘operating groups’ (in German: Betriebsgemeinschaften, abbreviated BG). The former sites in Ludwigshafen, Oppau, and Leuna now formed the Upper Rhein Operating Group (Betriebsgemeinschaft Oberrhein). The traditional name ‘Badische Anilin- & Soda-Fabrik’ was retained for heritage reasons.

Within the new corporation, Ludwigshafen, Oppau, and Leuna continued to serve as production centers for basic chemicals and high-pressure synthesis products such as nitrogen, methanol, and later fuel. Their initial relative autonomy began to diminish in 1929 when IG Farben was reorganized into divisions, each with its own sales and production structure. Oppau and Leuna were assigned to Division I (nitrogen, methanol, fuel, mining), while Ludwigshafen became part of Division II (organic/inorganic chemicals, dyes, rubber, pharmaceuticals, crop protection products).

Title of the company newspaper issue marking BASF’s 60th anniversary in April 1925

Birth of a Giant

The founding of IG Farben marks the culmination of long-standing tendencies toward concentration in the German chemical industry. Loose alliances had existed in the chemical industry since 1904, but the 1925 step was far more radical: the founding companies of IG Farben relinquished their legal independence. The goal was sweeping rationalization through streamlined production and distribution—and above all, greater competitiveness. During World War I, German chemical companies had lost their previously dominant position in the international market.

A key driving force behind the merger was BASF’s CEO Carl Bosch (1874–1940) [Link]. His ambitions extended beyond rationalizing the traditional dye business; he sought to secure the capital-intensive fuel synthesis project, BASF’s latest high-pressure initiative still under development. With 45 percent of total sales thanks to its fertilizer business and the sheer size of the Ludwigshafen/Oppau plants, the ‘old’ BASF was the largest single component of IG Farben in 1925. For this reason—and due to the scientific and technological expertise of his home company—Bosch claimed leadership of the new corporation. He served as CEO until 1935.

On one hand, Bosch’s strategic decisions transformed IG Farben into one of the world’s largest chemical companies with a broad product portfolio. On the other hand, he paved the way for cooperation with the Nazi regime, despite his personal rejection of its racist policies.

founding companies merged into IG Farben in 1925. The corporate logo featured the letters ‘I’ and ‘G’ inside a stylized flask.

Upper Rhine Operating Group: A Scientific and Technological Heavyweight

Its existing strengths made Upper Rhine Operating Group a heavyweight—especially when it comes to traditional BASF innovations and products in dye chemistry, intermediates, and basic chemicals. Added to this were new successes in the field of plastics. Particularly significant was high-pressure technology, which BASF introduced to the chemical industry in 1913 with ammonia synthesis. This gave Ludwigshafen/Oppau an internal monopoly on high-pressure synthesis technology within the group. The company’s unwavering commitment to the loss-making high-pressure process for fuel synthesis led IG Farben to seek state support, culminating in its cooperation with the Nazi regime in 1933.

Palace of Technological and Rational Modernity

280,000 cubic meters of volume containing 4,600 tons of steel: these figures impressed the public when IG Farben’s new headquarters in Frankfurt am Main was inaugurated in 1931. Corporate management, sales organization, and accounting were centralized here. The sheer scale of what was then Europe’s largest and most modern office building showcased to the world the monumental dimensions of IG Farben. Its architecture was intended to project rationality, strength, productivity, and self-confidence.

This satirical postcard from the early 1930s critically contrasts the overwhelming size of IG Farben with the mass unemployment caused by the Great Depression.

From Enemy Image to Cornerstone of Nazi Autarky

The notion that IG Farben helped the NSDAP or Hitler rise to power is a myth—both false and highly influential. During the Weimar Republic, the company faced hostility from various quarters, including the NSDAP. This included antisemitic attacks at both the Ludwigshafen site and the national level, portraying I Farben as the embodiment of an alleged ‘international Jewish financial conspiracy.’ This was fueled by the fact that many individuals on the company’s board of directors and supervisory board, as well as among its scientists, were Jewish or of Jewish descent.

Nevertheless, following the NSDAP’s electoral successes in late 1932, initial exploratory talks began regarding synthetic fuel production. In 1933, the company reached accommodation with the new rulers—out of calculation. For example, IG Farben’s chairman, Carl Bosch, was closely aligned with the democratic, liberal-civic DDP. He never joined the NSDAP. On the contrary, Bosch and other board members criticized the party’s antisemitism.

Even so, for business reasons, the company supported the Nazi autarky policy that Bosch had previously rejected publicly. Starting in 1933, strategic large-scale donations flowed to the NSDAP, with a smaller initial contribution in 1932 when the party first became the largest faction in the Reichstag. Personally, most of the company’s top managers initially kept their distance, with one exception (Wilhelm R. Mann). In 1933, three of the 17 regular board members belonged to the party. Additional memberships followed in 1937/38.

Board meeting break at IG Farben: Carl Bosch reviewing documents, around 1926 [Source: BASF Corporate History / Photographer: unknown]

A Fatal Partnership with the Nazi Regime

After the temporary dominance of nitrogen, the traditional sectors of dyes and pharmaceuticals remain the corporation’s main profit drivers. To secure its highly unprofitable fuel synthesis, IG Farben took advantage of the Nazi goal of autarky (economic self-sufficiency) in December 1933 with the so-called ‘Gasoline Agreement.’ Products from Upper Rhine Operating Group were also central to the Nazi regime’s rearmament plans. IG Farben and its Ludwigshafen/Oppau plants benefited significantly from this. The expansion of synthetic capacities for fuels and Buna (butadiene-sodium, a synthetic rubber substitute), accelerated by the ‘Four-Year Plan’ (1936), was only made possible through know-how and personnel from Ludwigshafen. These became among the corporation’s products that proved indispensable during World War II.

IG Sites Ludwigshafen/Oppau: Beneficiaries of Nazi Policy?

Even in the prewar years, IG Farben—and especially the Upper Rhine Operating Group—profited from Nazi economic policy. For example, overall sales trends for the company and its sister sites in Ludwigshafen/Oppau largely mirrored demand generated by the regime’s autarky and rearmament policies. However, the greatest profits were earned outside politically influenced sectors: in traditional dye and textile auxiliary products, where the Ludwigshafen plant maintained a strong position even after 1933.

Starting in 1936, as the Nazi economic bureaucracy began regulating and directing investments, funds flowed into the production of synthetic substitutes as well as armaments and, later, the war economy. Since IG Farben possessed essential know-how for these manufacturing processes, the company—and particularly the Upper Rhine sites—played a major role in these programs, financing most new production facilities from its own resources. IG Farben’s share in state investment plans was substantial, reflecting its dominant position within Germany’s chemical industry.

Nazification of Everyday Life

Far more than among workers, the NSDAP gained a foothold among white-collar employees. Staff members—and especially academics—at IG Farben in Ludwigshafen/Oppau held considerable influence in local party groups. The first NSDAP district leader in Ludwigshafen, appointed in 1932, was Dr. Wilhelm Wittwer, an engineer in Oppau. By contrast, the leadership of the Ludwigshafen/Oppau sites in the early 1930s consisted of middle-class, politically moderate conservatives. Only from 1938 onward are NSDAP members to be found in the site management: Carl Wurster and Otto Ambros, both of whom had entered the party in 1937.

From 1933 onward, Nazi ideology permeated everyday work life—through mandatory company assemblies, swastika flags, and the introduction of the authoritarian ‘Führer principle’ at the plant level. Employees were now classified as ‘followers’ and ‘plant leaders’ (Nazi terminology). Even the company newspaper (Von Werk zu Werk; in English: From Site to Site) abandoned its deliberately apolitical stance and became an ideological tool. The so-called Nazi ‘Council of Trust’ replaced the freely elected works council.

Four Faces of the IG Farben sites Ludwigshafen/Oppau

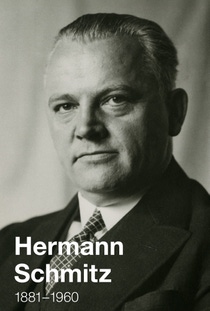

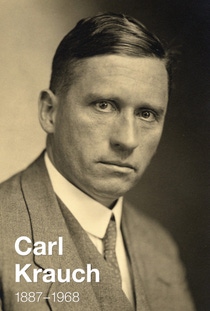

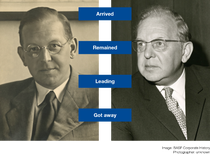

All of them made key career moves at the Ludwigshafen/Oppau plants or at the Leuna site in Merseburg. And all of them later became members of IG Farben’s board. Carl Bosch was succeeded as chairman in 1935 by Hermann Schmitz (1881–1960), and in 1940 as chairman of the supervisory board by Carl Krauch (1887–1968). Otto Ambros (1901–1990), by contrast, gained prominence through his central role in the Buna program.

The growing influence of the Upper Rhine Operating Group within the company was based on the importance of its high-pressure technology for Nazi autarky and rearmament. At the time of IG Farben’s founding in 1925, 27 percent of its board members (22 out of 83) came from the ‘old’ BASF; by 1945, that share had risen to 44 percent (10 out of 23 seats). For comparison: the two next-largest founding companies together accounted for 32 percent in 1945.

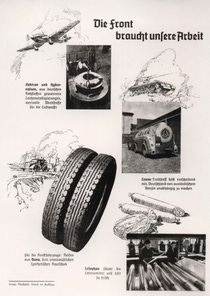

Pillar of Nazi War Policy

Without Leuna gasoline and Buna, the war would have ended quickly: These and other products from IG Farben were indispensable for the Nazis’ war of conquest and extermination. The Wehrmacht met its entire need for synthetic rubber for vehicle tires from the company’s Buna production. While IG Farben’s contribution to fuel supply was smaller, aviation fuel for the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) could only be produced synthetically using their process. The company also produced basic chemicals for further processing in various military applications, as well as chemical weapons, explosives, and their precursors.

IG Farben profited from the war economy and, especially, from the crimes of the Nazi regime. Across Germany and in occupied territories, the company participated in ‘Aryanizations’ (the expropriation of Jewish property).

Involvement in Crimes

The Nazis misused Zyklon B, originally developed as a pesticide, for industrial mass murder. Today, historical research indicates that the company’s top management was aware of this. The same applies to the ruthless exploitation of concentration camp inmates for the construction of the IG Farben plant at Auschwitz-Monowitz, where a company-owned concentration camp (Buna/Monowitz) was established in 1942 in cooperation with the SS. An estimated 25,000 inmates died as a result of forced labor for IG Farben. Forced laborers were also used at the Ludwigshafen/Oppau plants, with over 30,000 prisoners of war and civilian foreign workers from 34 nations—though not concentration camp inmates. These crimes were part of the IG Farben trial in 1947/48. The historical responsibility was denied by the accused and convicted for a long time.

IG Farben products for the war, including tires made from Buna and Leuna gasoline (excerpt from the company newspaper, December 1939)

High-Level visit to a war-critical IG Farben plant: Albert Speer, Reich Minister for Armaments and War Production, 1944 in Ludwigshafen (from left to right: Willy Liebel (Mayor of Nuremberg), Carl Wurster, Hermann Schmitz, Speer, Carl Krauch) [Source: BASF Corporate History / Photographer: unknown]

Over 30,000 Forced Laborers in Ludwigshafen/Oppau

As more German men were drafted into the Wehrmacht, the labor shortage grew. Conscripts, prisoners of war, foreign civilian workers, and especially concentration camp inmates were forced to fill the gap. Between 1939 and 1945, more than 20 million people were forced to work for the German Reich, over 30,000 of them in the IG Farben plants in Ludwigshafen/Oppau. There were no concentration camp inmates among them. The forced laborers came from all over Europe, mainly France, Italy, Poland, and the then Soviet Union. About one-third were women. The peak was reached around mid-1943, with over 13,000 affected—almost 35% of the total workforce. Forced labor was a public crime even in Ludwigshafen/Oppau. The large number of affected people was unmistakable and part of everyday working life for everyone employed there.

Especially Oppressed: Civilian Workers and Prisoners of War from Eastern Europe

Hard physical labor, undernourishment, catastrophic hygiene, humiliation, severe punishment: Civilian workers and prisoners of war from Poland and the German-occupied Soviet Union were subjected to the harshest conditions. Hidden solidarity and help from German employees were rare. To ‘discipline lazy foreigners,’ IG Farben established its own penal camp (Arbeitserziehungslager) on the Ludwigshafen site grounds in 1943. Over 400 people died during their forced labor at the Ludwigshafen/Oppau sites, most of them victims of air raids—due to lack of access to safe shelters.

Prisoners of war from Belgium (pictured, May 1940), France, Poland, the Soviet Union, and Italy (the latter as so-called military internees) were forced to work in the Palatinate IG Farben plants. [Image Source: BASF Corporate History / Photographer: unknown]

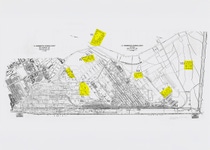

Cover trenches in the so-called communal camps—barracks camps for forced laborers—offered inadequate protection during air raids and even became death traps (site plan from 1944, marking and numbering of communal camps added later).

Late Reappraisal and Compensation

After 1945, forced laborers remained a forgotten victim group for a long time. Their utilization in the IG Farben plants in Ludwigshafen and Oppau was first publicly addressed by BASF in 1990. In 2002, forced labor finally became part of the scientifically researched company history ‘BASF: The History of a Company.’

In 1999, BASF became a founding member of the German Industry Foundation Initiative. A year later, together with the federal government, the Foundation Remembrance, Responsibility and Future (EVZ) was established, with BASF contributing around 70 million euros. Payments to former forced laborers were made from the foundation’s capital.

IG Auschwitz

About 25,000 people died in connection with the IG Farben plant at Auschwitz-Monowitz. The vast majority were Jewish concentration camp inmates. They perished due to inhumane living and working conditions on the construction site, in the infirmary, or during selections for the gas chamber. Auschwitz-Monowitz brutally demonstrates that forced labor was among the Nazi crimes against humanity. From October 1942, the company’s first concentration camp, Buna/Monowitz, existed on the IG Farben plant grounds in present-day Poland, under SS management. It became a model for satellite camps at major companies throughout the German Reich. The path to it began in 1941, when board member Otto Ambros selected the site for the fourth Buna plant near the Auschwitz concentration camp. He advocated for the use of inmates from the nearby camp. Ambros was responsible for the Buna complex of the new plant, while his board colleague Heinrich Bütefisch oversaw synthetic fuel production. Ambros was well-informed and visited the construction site eighteen times by 1944. Concentration camp inmates were also used at other IG Farben sites, such as Leuna.

Accomplices and Perpetrators

The entire IG Auschwitz complex was a place of dehumanization. Employees delegated from Ludwigshafen/Oppau became witnesses to the exploitation and physical destruction of concentration camp inmates—some even became perpetrators. The infamous selections of those deemed ‘unfit for work’ for gassing in Auschwitz-Birkenau were sometimes initiated or even carried out by IG Farben employees. In some cases, the threat of gassing was used as leverage for higher work performance.

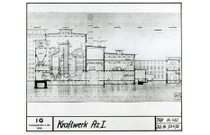

Construction drawing made in Ludwigshafen in 1941 for the power plant of IG Auschwitz

Planned in Ludwigshafen

All technical construction and design drawings for the Auschwitz-Monowitz plant were created in Ludwigshafen by Camil Santo, Erich Mach, and their teams in the construction and engineering design departments. Walter Dürrfeld, chief engineer from Leuna, became the technical director for building the Auschwitz-Monowitz plant. From 1941 to 1945, at least 300 employees from Ludwigshafen and Oppau worked there as chemists, engineers, foremen, skilled workers, and also as commercial or office staff, including women. Many returned to their home plants in the Palatinate afterward, bringing with them knowledge of the IG Auschwitz plant and its concentration camp.

Albrecht Weinberg at the grave of his family in the Jewish cemetery in Leer (East Frisia), 2023

Air War and Occupation

In 1943, the air war reached the IG Farben plants in Ludwigshafen/Oppau. Because of their strategic importance, they were high-priority targets for Allied bombers, especially Oppau, where aviation fuel and lubricants were produced. Between 1943 and 1944, production dropped sharply, and by 1945, operations had practically ceased. Ludwigshafen was less important for the war effort but was also heavily bombed. In 1944, the production of formaldehyde and textile auxiliaries essentially came to a halt, and by February 1945, the production of intermediates and plastics stopped as well. The war ended for the sites with the occupation by U.S. troops on March 23/24, 1945. Germany’s surrender followed on May 8. A devastating and shameful chapter of German history came to an end.

Dismantling and Liquidation

The Allies were aware of the symbolic power of the IG Farben building in Frankfurt am Main. After the war, it became the seat of the U.S. military government. At the Ludwigshafen and Oppau sites, rebuilding was the top priority and was accompanied by solidarity across hierarchies. The French forced administration and plans for dismantling were met with a sense of community. Everyday concerns focused on destroyed housing, insufficient food, and missing relatives. In Nuremberg, the management of IG Farben sat in the dock at the IG Farben trial from 1947 to 1948. In retrospect, the sentences were very mild. The company itself was dissolved by the military government. Its legal successor was IG Farbenindustrie AG in liquidation (i.L.), which existed until 2012.

Decades of Suppression

The longing for ‘normality’ in postwar German society initially prevented a reckoning with the recent past. BASF, newly founded in 1952, mirrored this widespread forgetting, suppression, and denial due to its lack of engagement with the Nazi history of the IG Farben sites Ludwigshafen/Oppau.Even in leading positions at the BASF Ludwigshafen site, people who had held responsibility at IG Farben until 1945 continued to work. Only with time and a generational shift did a new culture of remembrance gradually emerge at BASF and in society as a whole, starting in the 1980s.

File folder on the IG Farben Trial from the BASF Corporate History Collection

The five charges in the IG Farben Trial Before the U.S. Military Tribunal in Nuremberg

On the Defendant’s Bench: United States vs. Carl Krauch et al.

Twenty-Three: That’s how many IG Farben executives stood before the U.S. Military Tribunal in Nuremberg from 1947 to 1948. Although later viewed as very lenient given the weight of evidence, the 13 convictions sparked incomprehension and outrage among the German public. Another ten executives were acquitted for lack of evidence. The judges considered them followers and ordinary businessmen. The emerging Cold War also played a role in the verdicts: West German industry was needed again in the system conflict between East and West. The defendants felt unjustly accused. They suppressed, denied, and invoked ‘necessity of obedience,’ claiming they acted under duress. Convictions were handed down for looting and plunder in annexed and occupied countries (Charge II) or for slave labor and mass murder (Charge III). “To this day, I still don’t understand why I was convicted,” said Otto Ambros—found guilty under Charge III—as late as 1965.

A Plant in a City in a Country Without Perpetrators?

As elsewhere in the French occupation zone, denazification at BASF was probably neither rigorous nor complete and was sometimes openly lenient. Here too, neighbors, friends, and colleagues issued each other certificates of harmlessness (‘Persilscheine’). Of about 23,000 people who had to fill out a questionnaire about their political involvement, around 6,000 were summoned before the ‘Cleansing Commission BASF/IG Farben. ’ Later, responsibility for the proceedings passed to arbitration chambers. Although the data is incomplete, a clear trend emerges: Only six percent of all cases actually tried resulted in dismissals due to serious political involvement.

Denazification questionnaire of Carl Wurster

A Seemingly Harmless Greeting Card

In the first postwar decades, looking back at the IG Farben era revealed a divided memory: Scientific and technical achievements were claimed as part of the history of the newly founded BASF in 1952. However, the associated political and social circumstances—or even crimes—were ignored. This is exemplified by the hand-painted greeting card for Camil Santo’s retirement in 1955, who had led the Ludwigshafen construction department since 1932 and, even as a retiree, oversaw the completion of the BASF high-rise until 1957. In the proudly presented series of sites whose construction or expansion Santo oversaw, Auschwitz appears on the greeting card without further comment (highlighted in the adjacent illustration for clarity).

Carl Wurster: A Reassessment

Carl Wurster assumed leadership of BASF AG when it was reestablished in 1952 and remained at its helm until 1965. Colleagues and the broader public saw him as a doer, a charismatic yet approachable business leader. With increasing distance, a more complete and critical picture emerges. Wurster stands for reconstruction, the economic miracle years, and new successes, but also for the many personnel continuities from the Upper Rhine Operating Group to the new BASF. This intertwining suggests a new interpretation of Wurster: as someone who denied, minimized, and glossed over both his own responsibility and that of IG Farben during the Nazi era.

Changing Remembrance Work

Do you have any questions about our corporate history?

Reach out to the BASF Corporate History team.